Gender Transformative Approaches (GTA) are strategies that go beyond a focus on individual change for women, girls, and marginalized groups and aim to transform unequal relations that reinforce gendered inequalities. GTAs don’t just include women as participants or beneficiaries of support – instead they integrate gender issues into all aspects of program and policy design, development, implementation, and evaluation (National Information Platforms for Nutrition: n.d.).

Importantly, GTAs take an intersectional and context-specific approach, recognising that some groups are more disadvantaged due to the link between gender and other forms of oppression (such as economic status, disability, ethnicity, sexuality, among others) (Girls Not Brides: 2023). In order to replace unhealthy norms with redefined healthier ones, GTAs try to address the misalignment between people’s individual attitudes and their actions and behaviours and attitudes (Aventin et al: 2021).

GTAs aim to accomplish three things (ACT for Youth Centre for Excellence: 2014; Baird et al: 2022; Bartel et al: 2022):

- To identify, raise awareness about, and critically examine unhealthy gender norms, gendered systems, and institutional practices;

- To question the costs of adhering to these norms; and

- To replace unhealthy, inequitable gender norms with redefined healthy ones.

The focus of GTAs can vary, but many GTAs focus on tackling gender relations, power, and violence, and tackling discrimination in terms of “opportunities, resources, services, benefits, decision-making, and influence” (aidsfonds: 2020). GTAs can take the form of community-level or individual-level interventions (Johnson et al: 2023). Based on MacArthur et al. (2022) GTAs have five key principles:

- They are motivated towards profound gender-transformations.

- Focused on the systems which perpetuate inequalities.

- Grounded in strategic gender interests.

- Recognising and valuing diverse identities.

- Embracing transformative methodological practices.

GTAs seek to challenge the institutions and systems that uphold inequality. This can require changes to the policies, laws, norms, and practices that are in place and that underlie existing gender inequality (aidsfonds: 2020).

GTAs are important because they seek to remedy rigid social norms that limit progress in terms of gender inequality. Thus, they have the potential to create substantive and long-lasting progress towards gender equality.

The Social-ecological model

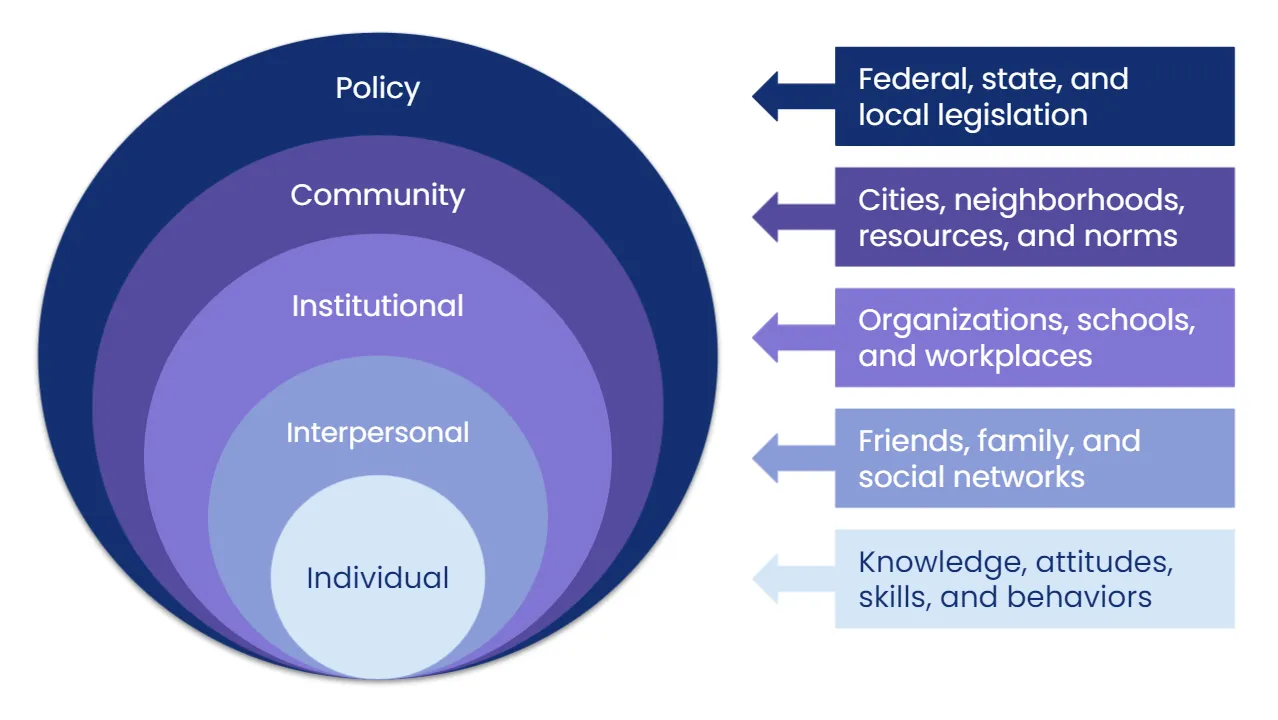

The Social-ecological model, helps people working in the field of gender transformative approaches by enabling them to understand the relationships between individuals and others, and thus to see how these relationships might be shifted or changed.

Image source: https://kasleykillam.medium.com/the-inspiration-behind-community-microgrants-5bdedff5e48a

As the image shows, the social-ecological model looks at:

- Individual level: knowledge, attitudes, skills and behaviours

- Interpersonal level: the influence of relationships such as friends, family, and social networks.

- Institutional level: the influence of organizations such as schools, and workplaces.

- Community level: the influence of cities, neighbourhoods, resources, and norms.

- Policy level: the influence of laws and policies at the local, regional, and national level.

By understanding the interplay between these various levels, it is easier to see how formal and informal rules and practices enable or constrain individual agency.

Gender transformative health interventions focus not only on norm change at the individual, cultural and interpersonal level, but also in a person’s environment (e.g. school, workplace, family, health centre, community, media, government, etc.). In this way, the structural environment that can constrain or enable the agency of men and women to make positive change is considered (Dworkin et al 2015).

Research on SRHR programmes has shown that working simultaneously on the different levels of the socio-ecological model is more effective than focusing on interventions at a single level. A meta evaluation of the World Health Organization (WHO) provides evidence that gender transformative SRHR programmes that address gender inequality at the individual, community and institutional level simultaneously have better outcomes than programmes that ignore the surrounding environment (WHO 2007).

Working to promote sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) includes a focus not only on sexual illness, but also on full access to and enjoyment of sexual wellbeing and sexual health.

This can include a focus on:

- Promoting access to safe and quality abortion services and treatment of unsafe abortion;

- Detecting and preventing sexual and gender-based violence;

- Promoting access to antenatal, childbirth, and postnatal care;

- Providing counselling and services for infertility;

- Detecting, preventing, and managing reproductive cancers;

- Providing comprehensive sexuality education;

- Providing counselling and services for modern contraceptives;

- Working to end female genital mutilation; and

- Preventing and treating HIV and other sexually transmitted infections.

GTAs are useful in promoting sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) because they are grounded in an understanding of local contexts, thus facilitating solutions that are relevant and long-lasting.

Taking a gender transformative approach to sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) has a dual focus on improving access to health and health services and changing gender norms (Fisher and Makleff: 2022).

This can entail (Aventin et al: 2021; Bartel et all: 2022, Dworkin et al: 2013; Equimundo: 2021; Kato-Wallace et al: 2019; Lees et al: 2019; National Information Platforms for Nutrition; Ncube et al: 2022; Rutgers: 2018; UNICEF: 2023):

- Promoting the relative position of women, girls, and marginalized groups including LGBTQ+ persons, and to encourage men’s roles as enablers of the health and wellbeing of these groups;

- Encouraging participants to critically question the social expectations for women and men, and their impact on their roles as partners;

- Challenging homophobia and gender-based harassment;

- Addressing harmful norms of masculinity that link to heterosexual sexual prowess and gender-based violence;

- Promoting shared decision-making between males and females;

- Addressing the power relationships between women and others in the community, such as service providers and traditional leaders;

- Challenging norms around contraceptive use (e.g. that ‘real men’ don’t wear condoms, or that women should not carry condoms);

- Changing gender norms and attitudes in influential social groups to leverage their influence as agents of change in their communities and peer groups;

- Empowering women/girls and people with diverse sexual orientation, gender identity, gender expression, and/or sex characteristics;

- Identifying and addressing community power structures that prevent women from making decisions about their own health including family planning, health/nutrition services; and

- Working to change laws and policies that promote gender inequitable access to sexual and reproductive health.

Gender transformative change can be observed at three levels: the individual, relationships, and norms and structures (Morgan: 2014). Change is often measured relative to a baseline or control group. Evidence can be gathered through qualitative or quantitative measures.

At an individual level, gender transformative change in an SRHR program can be measured by, for instance, a decrease in the incidence of gender-based violence, a decrease in controlling behaviour by an intimate partner, and an increase in communication about sexual behaviour (Morgan: 2015). In addition, it may include measuring changes to assets and earnings, or changes in individual livelihood choices or practices. It could also be measured at the level of knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs – for example, greater levels of awareness about SRHR issues, or a understanding of the consequences of limits to SRHR.

At the relationships level, “gender transformative programs attempt to go beyond measuring individual-level changes to measure the social changes involved in advancing gender equality, including changes in relationships” (Morgan: 2014; 8). Thus, programs try to capture changes in intra-household relationships (for example, between spouses, intimate partners, or parents and children) and relationships outside the household (for example, between and among groups of people). Examples of indicators might include a decrease I family conflict, an increase in spousal/family communication, an increase in joint decision-making among partners, more equitable treatment of children., or increased support within a community (Morgan: 2014). Although the changes might occur at the level of the individual, the impact of the change may have an impact on other relationships that the individual is a part of.

A central tenet of GTAs is that changes must occur at the level of norms and structures for a change to be truly gender transformative. Achieving gender equality requires changes to macro-level gender relations, and broader social norms and structures. Measures might include changes to law and policy or changes in attitudes in societal attitude surveys. However, measuring change at this level is more difficult than at the level of individuals or relationships.

Gender transformative change can also be measured by looking at indicators across three areas of empowerment (Hillenbrand et al: 2015):

- “Agency: Individual and collective capacities (knowledge and skills), attitudes, critical reflection, assets, actions, and access to services.

- Relations: the expectations and cooperative or negotiation dynamics embedded within relationships between people in the home, market community, and groups and organizations.

- Structures: the informal and formal institutional rules that govern collective, individual, and institutional practices, such as environment, social norms, recognition, and status.”