So, this happened… in May 2023, Namibia’s Supreme Court passed a progressive ruling that its government must recognise the unions of same-sex couples concluded in foreign countries where it was legal to do so. Though this step is recognised as somewhat progressive, for Namibia it is a bit of a conundrum due the fact that same-sex marriage remains illegal in Namibia itself. Sexual relations between men are still considered a criminal offence in Namibia, however the law is seldom enforced in this respect.

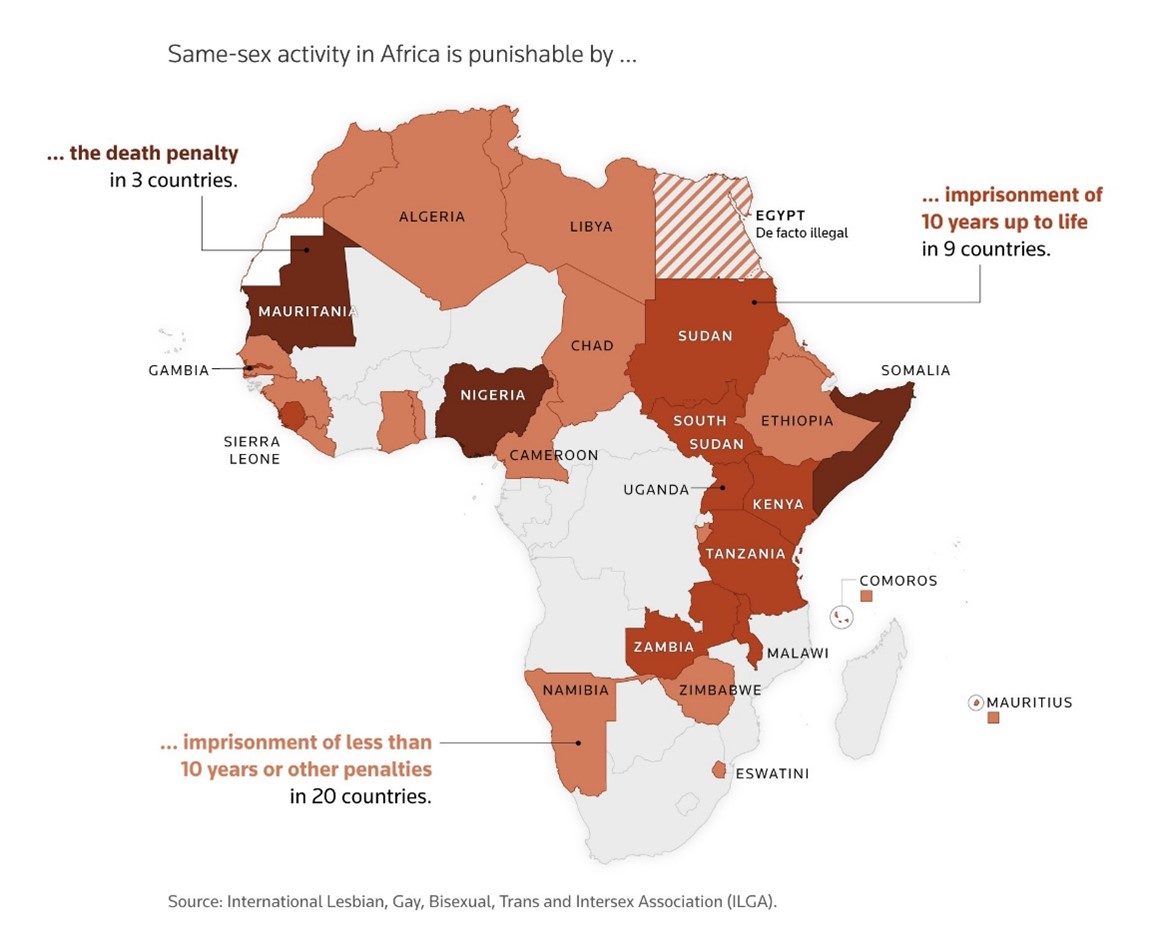

This ruling is in contrast with the developments in Uganda, in the same month of May 2023, the legislature promulgated one of the harshest anti-LGBTIQ laws to date. The new law punishes what it calls “aggravated homosexuality” with the death penalty, criminalises transmission of HIV/AIDS through gay sex and prescribes a 20-year sentence for “promoting” homosexuality. Same-sex relations were already illegal, not only in Uganda and Namibia alone, but in more than 30 African countries altogether. In other countries like Mauritania, Somalia, and some Nigerian states that practice Sharia law, lengthy prison terms and capital punishments are commonplace. The illustration below indicates about 32 nations in Africa that have outlawed same-sex relationships:

According to ILGA’s database, same sex relationships are considered legal in 22 African countries. Out of these 22 only 12 have never adopted laws criminalising same-sex relationships.

Historically, people with diverse gender identities have always existed in African societies, however their visibility was always on the margins and tolerance in society has always varied. There are several factors that have influenced the current and existing narratives around same-sex relations, mainly the influence of Christian and Islamic faiths under European and British colonial rule and modern African electoral politics.

Much of Africa’s anti-same-sex legislation originated during colonial rule. Several studies show that Europeans viewed Africans’ traditional sexualities as examples of their supposed racial inferiority, and anti-LGBTQ+ legislation served as one of the means of subjugation. In addition, Christian fundamentalists and seemingly all major schools of Islamic law condemn homosexuality, and both religions have millions of believers in Africa.[1] As a result religion has been and continues to be an important factor in forming many of society’s opinions about sexual behaviours to date. Sadly, this influence has largely been negative and patriarchal in nature. The Christian response to the subjects of sex and sexuality has been that sex is taboo, it is not to be talked about openly, viewed as ‘dirty’ and sexual urges must be oppressed unless its solely for procreative purposes and it occurs within a heterosexual marriage. Thus, sex is used as a tool for control and power.

Our societies have tended to glorify domination in relationships. One is considered successful based on the amount of power they wield over another. This type of power is about supremacy, force, control and is largely motivated by fear. It is the desire for and the persistence of domination [unequal power] in our relationships that is the root of most of the abuse and violence that exists in society today. The LGBTQ+ community has been the target of discrimination and violence by several religious groups in many African countries. This has resulted in exclusion and marginalisation of thousands of people.

And because power does not exist in a vacuum we have and continue to experience African leaders that use[ed] anti-LGBTI rhetoric to gain support and distract from their shortcomings. They often push for more repressive anti-LGBTQ+ policies during election campaigns, often labelling LGBTQ+ identities as a Western import that threatens social cohesion. These leaders leverage fear to divide and maintain power by demonstrating an ever-increasing for cruelty especially to those seen as ‘weaker’, poor and/or marginalised.

We have now come to understand that sexual behaviours and cultural norms are interconnected, and it is through culture that people learn how to act, what to say and how to understand the world around them. Cultural practices are powerful drivers of behaviour because these are norms and standards people live by. These are the shared expectations and rules that guide the conduct of people within particular social groups.

To address the challenges that we face today we must invite people into a process of unlearning the culturally supported desire for ‘power over’. There are other forms of power that are better. Power with: which is built on mutual respect, understanding and solidarity. It is more about collaboration and requires us to place value on the mutuality of our relationships and help people recognize that we are all interdependent on each other. Power to: is about recognising the unique potential of every individual to make a difference, to shape their life, to be alive to new possibilities. Power within is about recognising the self-worth and the ability to recognise difference while respecting others. These types of powers are in alignment with the traditional concept of ‘ubuntu’ [Zulu] [also known in other languages as hunhu(Shona), Utu (kiSwahili) Ajobi (Yoruba) Botho(Tswana)] which is about harmony, cooperation, being of service to and for one another, mutual respect. Ubuntu implies a constant awareness of one’s beingness and that he/she/they as they interact with others in the world, they effectively represent the people from the country/place of origin, and therefore are compelled or obligated to conduct themselves according to the highest standards and exhibit the virtues upheld by their people.

There is no doubt religion has played a major role in shaping our understanding of sexuality and interactions with others. Despite contributing to the distortions around sexuality, religions also contain important responses for addressing the historical injustices that haunt our societies today. They hold a major role in establishing the values of grace and compassion, both which help us move toward an attitude and acceptance that we are all human. It is through our common goals for a shared humanity that we can reconstruct our ideals about social and sexual injustices. We need to close the gap between church teachings and real-life experiences. This must be done by working within the traditional religious values, while working beyond the traditional patriarchal patterns.

A growing number of countries are legalizing same-sex relationships. South Africa became the first African country to legalize same-sex marriage in 2006. The 1996 South African constitution has enshrined the rights of everyone including protection against discrimination based on sexual orientation. Thus, South Africa is one of only twelve countries in the world, and the only one in Africa, to explicitly protect LGBTQ+ people in its constitution. These protections and consequent policies have helped pressure some of its neighbours into rolling back anti-LGBTQ+ legislation. Mozambique in 2015, dropped a colonial-era clause outlawing same-sex relationships from its penal code. Botswana’s High Court made a similar move in 2019, replacing a law that had dated back to 1965 when the country was under British rule. Similarly, Angola in 2021, became the latest African country to decriminalize same-sex relationships, after passing a new law to replace one that dated back to the colonial era.

There is still much work to be done to create an environment in which all person’s rights are respected and where we call all live in peace and harmony, without fear, prejudice, and discrimination.

These narrow and stigma laden views on sexual diversities points to a targeted backlash against advances in gender transformative efforts. This, at a time when all countries have signed up on the all-important SDG agenda. An important intervention premised on the notion of ‘leave no one behind’. Sadly, this statement does not seem to apply to the LGBTQIA+ community.

We all must work tirelessly to turn the tide against this attempt to undermine fundamental rights of the minorities among us. An injury to one, is an injury to all as the youth of South Africa taught us. Human rights are indivisible!

Freedom is not something that one people can bestow on another as a gift. They claim it as their own and none can keep it from them.

Kwame Nkrumah

[1] Adamczyk, A., & Hayes, B. E. (2012). Religion and Sexual Behaviors: Understanding the Influence of Islamic Cultures and Religious Affiliation for Explaining Sex Outside of Marriage. American Sociological Review, 77(5), 723–746. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122412458672