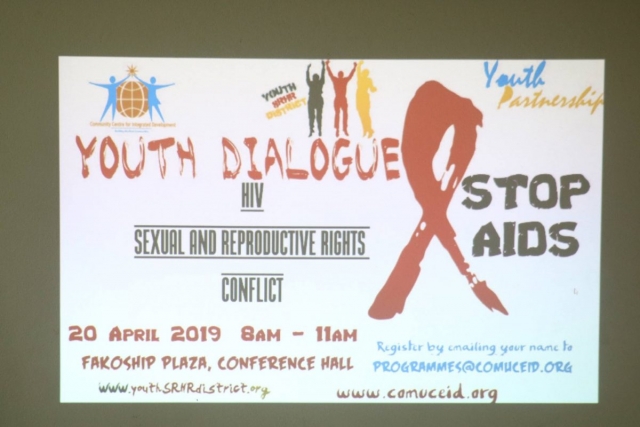

On the 20th of April 2019, Community Centre for Integrated Development (CCID), the Secretariat for MenEngage Cameroon, held a discussion with young leaders on how conflicts impact the sexual and reproductive health and rights of young people, with HIV being the main focus. The discussion put on the spotlight how conflict puts individuals at higher risk of contracting HIV due to potential for sexual violence, disruption of health services, forced displacement, increased poverty, placing girl children at the risk of forced and early marriage, thus exposing them to potential HIV infection. Child brides are more likely to contract HIV as their older husbands often have more sexual partners. They are more likely to experience domestic violence, and child marriage often takes girls out of school and programmes which educate about protecting one’s self from HIV.

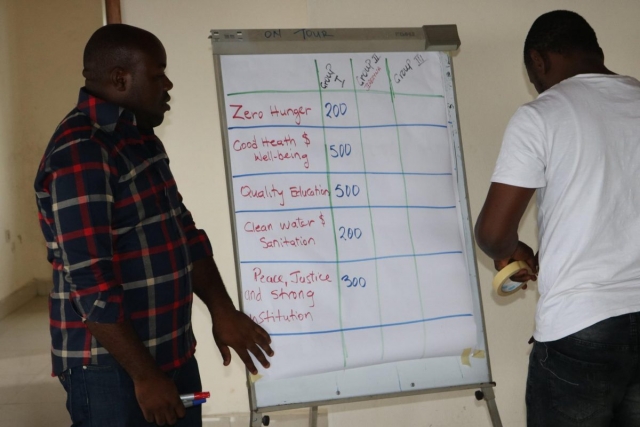

Both conflict and child-marriage are challenges faced by Cameroon at this time, and are both proven to increase rates of HIV and make it harder for those living with HIV to access treatment. The recommendations that came out of the workshop included:

- Donors, national governments, policy makers, and programmers should ensure that the basic needs of families are met as one of the most effective means to mitigate the risks of child marriage during emergencies. Families consistently identified poverty as a primary driver of child marriage during and immediately after conflict or displacement. Existing research identifies the transformative power of economic interventions in reducing child marriage practices. Families must be able to feed, clothe, house, and protect their children in order for there not to be a perceived benefit in marrying their daughters out of the family at early ages.

- Donors, national governments, policy makers, and programmers should invest in girls in order to build and/or reinforce girls’ intrinsic value within communities. Resources for child-marriage interventions should focus on girls: providing health, education and/or livelihood opportunities; teaching life-skills and decision-making; and/or fostering economic literacy. In particular, research highlights the importance of education in protecting girls from child- marriage. However, barriers to accessing school (distance, language, curriculum, fees), as well as other education and skills programming, persist in many humanitarian contexts and, in all cases in this research, were connected to child-marriage decisions.

- Programmers should ensure that adolescent girls, including child brides and adolescent mothers, are identified and reached with programming. Adolescent girls are a diverse group with unique needs, whether out of school, orphans, married and/or parenting, living with disabilities or caring for family members who are disabled, or heads of household. In order to reach them, it is critical first to know who and where they are. Donors and programme planners should engage in mapping activities and consultations to ensure identification of, and engagement with, the many adolescent girls in need of support.

- Policy makers and donors should recognise that child-marriage is best addressed across a variety of sectors, and designing and implementing child-marriage interventions is complex.Rarely do the root causes of this practice, which research shows are diverse, fall under the auspices of only one sector. Effective interventions require co-ordination across a variety of sectors, and should be developed based on existing learning from development contexts. Actors from education, livelihoods, health, and protection are all critical to discussions and planning around preventing and responding to child-marriage. Although interventions may most often be designed by those working on gender-based violence (GBV), much of the implementation and monitoring needs to be done by other sector actors. The new Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC) guidelines on the prevention of GBV provide practical steps for how various sectors should be involved in prevention of all forms of GBV, and funding must be made available to support this model.

- Policy makers and donors should understand the importance of, and provide support to, as well as assessment and adaptation. As crises move beyond the acute emergency phase, interventions to address child-marriage within a displaced community will need to address the many nuanced factors that may be impacting child-marriage decisions within that community. This research highlights the importance of understanding context and diversity of displaced populations through participatory assessments with a diverse group of community members, including gate-keepers. While girls are the primary beneficiaries, programmes cannot ignore the influential persons in their lives or the environment around them. This includes engaging mothers, fathers, husbands, and community leaders in assessments and possibly in engagement strategies prior to, or during, planned interventions. Additionally, it is critical that the humanitarian community examine existing tools and determine whether they are sufficient for understanding these complexities, or whether there is a need for revisions or the development of new tools specific to this issue.

- Donors and policy makers should support the piloting of child-marriage interventions and the documentation of learning. Evaluation research has identified promising interventions, but research is lacking on how these can be integrated within emergency response. In humanitarian contexts, approaches to preventing and responding to child-marriage should be piloted and specifically monitored for child- marriage outcomes, including: skills and asset building of adolescent girls; parent and community education; economic interventions for household self-reliance; improving access to education; and outreach strategies to married girls, inclusive of comprehensive health and livelihoods programming.

More information about our project can be found at from youthsrhrdistrict.org. Youth SRHR District is an online platform that publishes information about sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) for young people. We seek to empower youth and build their capacity to empower others through education and advocacy.